I love eating food that’s been sitting around half a year.

I’ve written before about the preservative power of black pepper–you can read it here.  Pepper’s antimicrobial properties might explain this recipe called “To Make Pepper Cakes That Will Keep Good In Ye House For a Quarter or Halfe a Year” from Martha Washington’s, “A Booke of Cookery,” which was given to her by her husband’s family on the occasion of her first marriage in 1749. It is believed that the text was transcribed in Virginia, sometime in the latter half of the 17th century.

Take treakle 4 pound, fine wheat flowre halfe a peck, beat ginger 2 ounces, corriander seeds 2 ounces, carraway & annyseeds of each an ounce, suckets slyced in small pieces a pritty quantity, powder of orring pills one ounce. worked all these into a paste, and let it ly 2 or 3 hours. after, make it up into what fashions you please in pritty large cakes about an intch and halfe thick at moste, or rather an intch will be thick enough. wash your cakes over with a little oyle and treacle mixt together before you set them into ye oven, then set them in after household bread. & thought they be hard baked, they will give againe, when you have occasion to use it slyce it & serve it up.

Allow me to offer some quick, 18th century translation services: Treakle is molasses and suckets are candied fruits: lemon or orange peels, or citron, another citrus fruit. Â Culinary historian Karen Hess points out that this recipe is in fact for gingerbread, and reflects a holdover from the Middle Ages: a time when pepper was used the same as any other spice, in the sweet as well as the savory. Although this recipe doesn’t list pepper in the ingredients, Hess argues it may have been omitted accidentally.

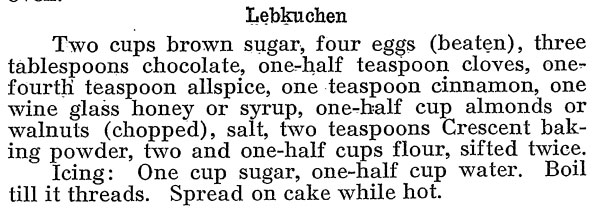

I was curious if these “Pepper Cakes” really did taste better after six months. Â This recipe is like a proto-fruitcake or lebkuchen.

I decided to add a quantity of pepper equal to the ginger. When working from historic recipes, it’s always helpful to translate the ingredients, scaling down the proportions to make a smaller recipe. I call this step “Make a plan!”:

1 pound (about 2 cups) Molasses

4 cups Flour

1/2 ounce (3 tablespoons) Pepper

1/2 ounce (3 tablespoons) Ginger

1/2 ounce (3 tablespoons) Coriander

1/4 ounce (1 1/2 tablespoons) Caraway

1/4 ounce (1 1/2 tablespoons) Anise Seed

1/4 ounce (1 1/2 tablespoons) Dried Orange Peel

1 cup candied fruit

To recreate this recipe, I used Hecker’s Unbleached Flour, which has been in production since 1843.  There are stone ground, 18th century flours available on-line, but I decided this was a decent substitute for my purposes.  To four cups of flour, I added my spices, starting with ½ ounce course ground Lampung pepper, the variety I suspect would have been available when this recipe was written.   ½ ounce is a surprisingly large amount of spice–about three tablespoons.  Ginger and coriander went in next, followed by caraway–I used both ground and whole caraway seeds to add texture.  I was unable to find anise seeds, so I substituted the similarly licorice-tasting fennel seeds, which I pounded with the dried orange peel in a makeshift mortar and pestle: a muddler and a measuring cup.

After the dry ingredients, I added the molasses, and stirred the bowl into a deep brown goo.  Only then did I realize I forgot the suckets. “Oh fuck it! The suckets!†I declared, to no one at all.  I had picked up a contained full of “fruit cake†type fruits; the typical holiday blends includes the 18th century favorites lemon peel, orange peel, and citron.  Fruitcake  is probably the only time we use citron in modern cooking; not many people even know it’s in there. Now you do.

I folded in a cup of suckets, realizing that this wasn’t the most accurate historic food recreation I had ever rendered. True culinary historians are probably reading this and gritting their teeth.  I covered the dough with a towel, and set it aside for a few hours, as the original recipe recommends.

When I returned, it had formed into a sticky, solid mass.  Here is where the original recipes gets vague.  The authoress says: “make it up into what fashions you please in pritty large cakes about an intch and halfe thick at moste, or rather an intch will be thick enough.† Pritty large cakes?  How large is “pritty largeâ€?  And in comparison to what?  Or “pritty” like lovely? Lovely cakes?

I floured a board, and rolled the dough to about an inch thick.  I cut out some preeeeeetty large cakes, about 4 ½ inches in diameter.  That’s preeeeetty large, right?  The cut cookies went on to a parchment lined baking sheet, and I brushed the top of each one with a mixture of a little molasses and almond oil.

The baking instructions read: “set them in after household bread.† Bread bakes at around 450 degrees; so I preheated my oven to 450, and let the pepper cakes bake for 20 minutes.  Then, in an effort to simulate a wood-burning oven cooling as the fire goes out, I turned the oven off and left the cookies inside.

About an hour later the oven was completely cool, and I pulled the cookies out, glossy from their caramelized molasses top coat.  I nibbled on one, still slightly warm, and the flavor was so strong it was like a punch in the face.  It was, in essence, pure spices held together by a little flour and molasses.  I suspected that like a modern fruitcake (or their closer relation, lebkuchen), these cookies might taste better with age.  So I took the recipe title’s recommendation, and locked the cakes away in a tin, to be tasted in six months.

I first baked this recipe at the end of July, so the time has come. Â I had to save the cookies from being thrown away TWICE by well-meaning roommates. Â After being entombed for so long, the cookies looked and tasted like the 17th century: dark and spicy. Â They weren’t revolting like they were in August, they were revolting in an entirely new way. Â Chewy and stale, the candied fruits were unappealing. Â The explosive flavors of the spices were interesting, and widely varied as I slowly chewed the cake. Â But if this was good eating 300 years ago, I feel sad for the 1700s.

The original American Christmas cookie. Recipe here.

The original American Christmas cookie. Recipe here.