A glass-like maple brittle.

A glass-like maple brittle.

The warming weather means the end of maple sugaring season. It’s not a sad thing, it just means it’s time to enjoy the spoils!

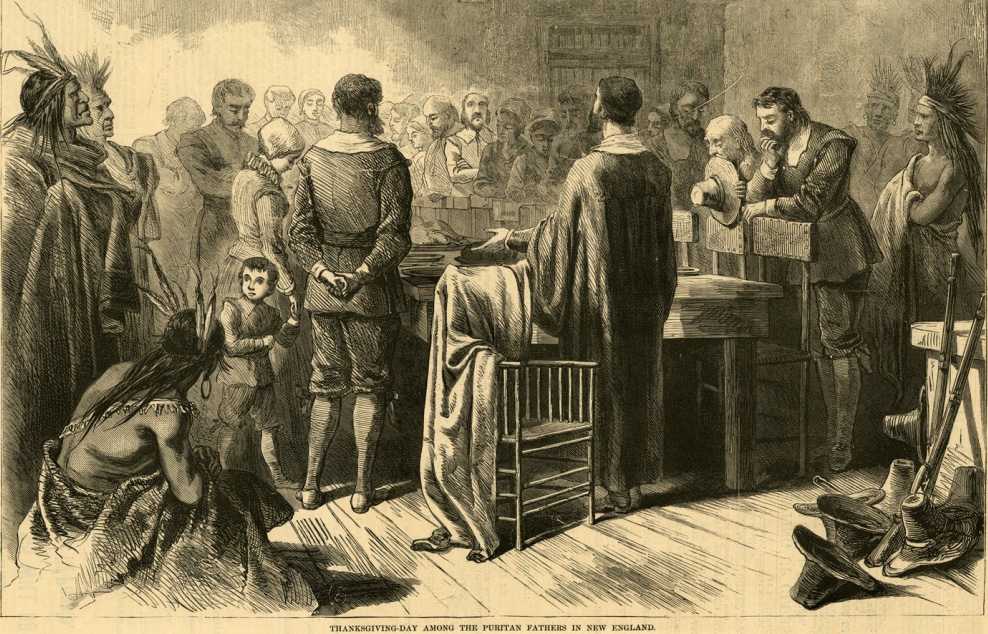

I’m experimenting with a recipe for Maple Sugar Brittle for an upcoming family event at the New-York Historical Society. Now through August 2014 they have an exhibit up called Homefront & Battlefield: Quilts & Context in the Civil War. The primary focus is on 19th century quilts, but it looks at larger material culture with items like a pattern for a homemade mitten–with the index finger separated for a trigger finger.

Trigger finger mittens.

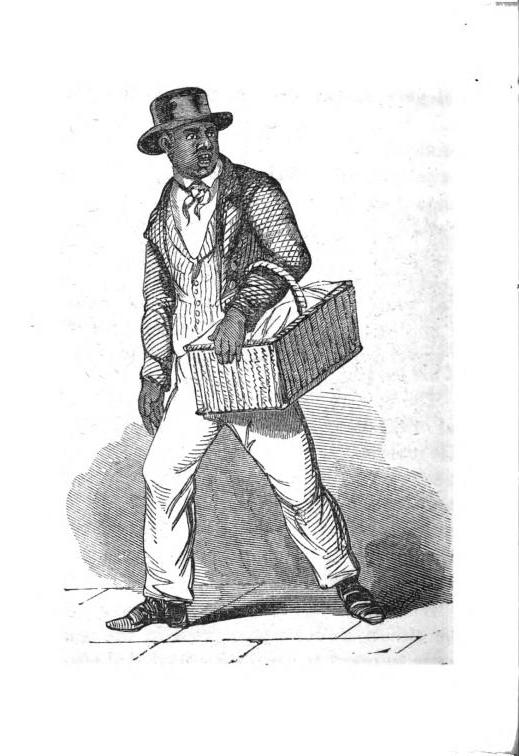

Free labor dress: noble, if a little dowdy.

One item I found particularly interesting is the “Free Labor Dress,” a dress made from cloth not produced by slave labor. Before and during the Civil War, advocates in the North were choosing clothing made from wool, silk, linen in an effort to not support slavery. Cotton was only used when it was certified from a free labor source.

There’s a parallel to this idea in food: many people encouraged the use of maple sugar instead of cane sugar. Cane sugar was also produced on plantations using slave labor, while maple sugar was made in the North by “…only the labour of children, for that which it is said renders the slavery of the blacks necessary,” as Thomas Jefferson put it. Yep, it only took underage farm children hours of collecting sap and boiling it down to make maple syrup.

With this idea in mind, I uncovered a recipe for Molasses Candy by Catherine Beecher. Catherine, a famous cookbook writer in the 19th century, was the sister of Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Her brother, Henry Ward Beecher, was also an fervent abolitionist. And although not as outspoken on abolition as her siblings, Catherine does suggest the use of maple syrup instead of cane molasses in her candy recipe.

Molasses Candy, from Miss Beecher’s Domestic Receipt-book, 1871.

I’m working on a fussier interpretation of this recipe, but in the meantime, I stumbled upon a process that’s quite simple and exceedingly delicious.

To make my maple sugar candy, I boiled maple syrup on high heat until it began to darken. While the sugar was boiling, I greased a rimmed baking sheet with spray Mazola oil, and spread roasted, salted nuts in an even layer. Catherine suggests roasted corn–we know it better as “corn nuts“–which I think would make an awesome brittle.

I poured the maple sugar over top of the nuts and then used a fork to press and then gently pull the sugar and nuts into a thin layer. The sugar is very stretchy after just a moment of cooling and gives you plenty of flexibility before it gets too brittle.

After the sugar was cool to the touch, I broke it into pieces with my hands. Done. Super simple, super beautiful, and incredibly delicious.

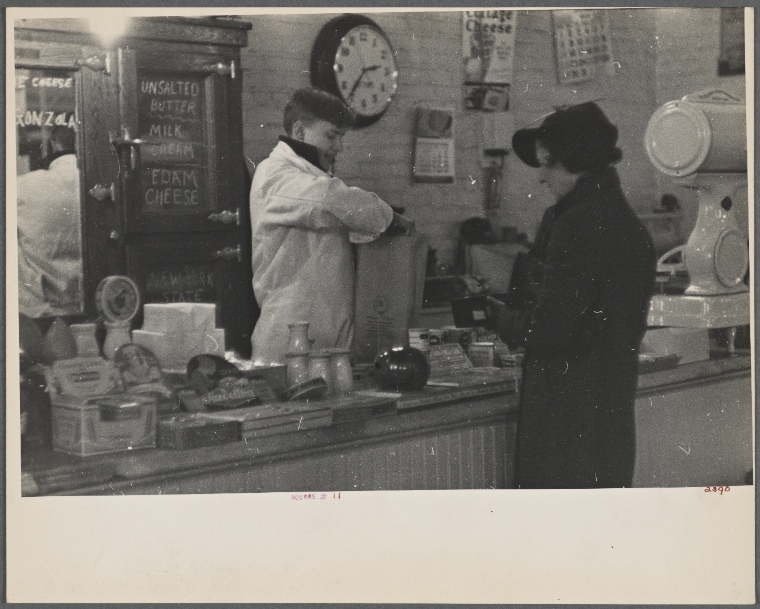

Interior of a grocery store, 1936. Source:

Interior of a grocery store, 1936. Source:

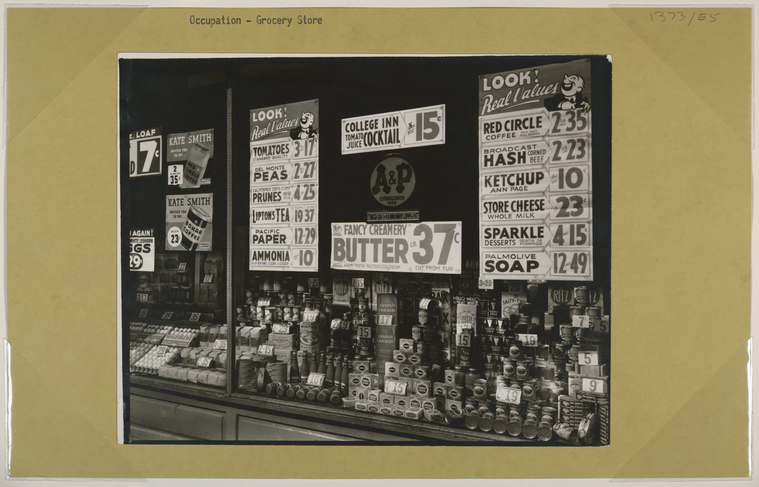

A&P, 1936. Source:

A&P, 1936. Source: