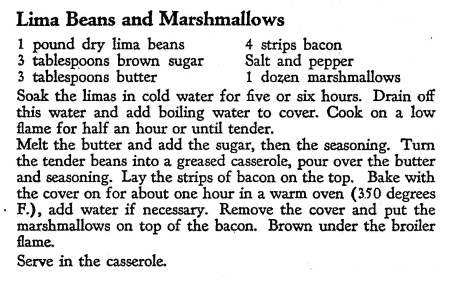

Lima beans, bacon and marshmallow casserole. Photo by Jess Tsang.

Lima beans, bacon and marshmallow casserole. Photo by Jess Tsang.

Coming to a holiday table near you: Lima bean and bacon casserole, topped with marshmallows! Ok…maybe not. This recipe comes from a handwritten booklet my Mom sent me. She said she “took a chance!” and bought it on Ebay, and when I flipped through the thin and faded notebook, this recipe caught my eye for obvious reasons. With such an odd combination of ingredients, I had to give it a shot.

The History

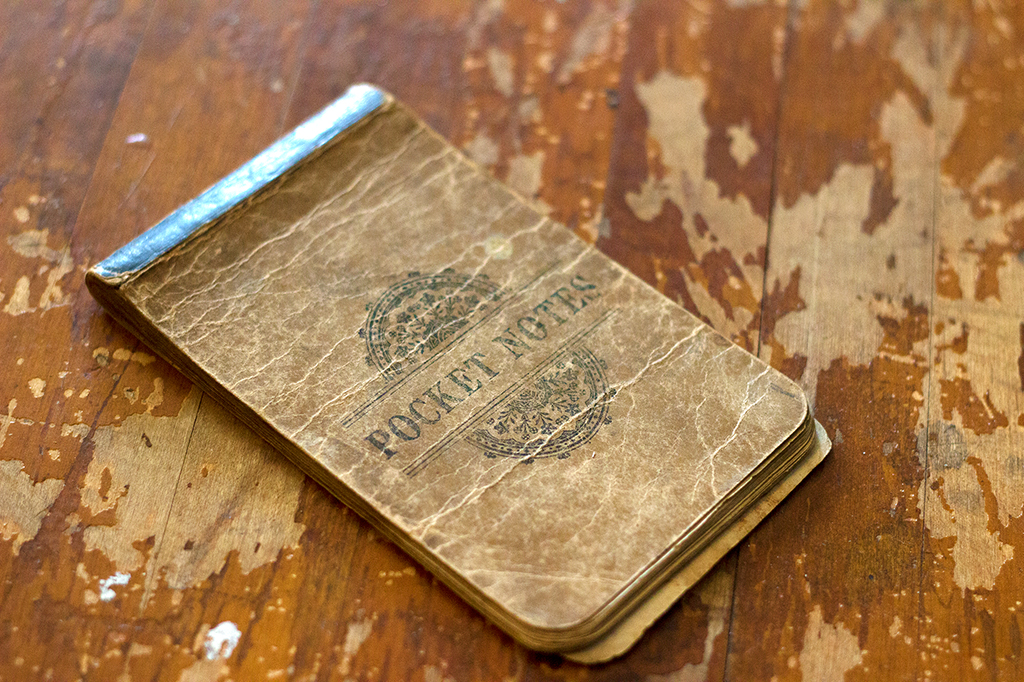

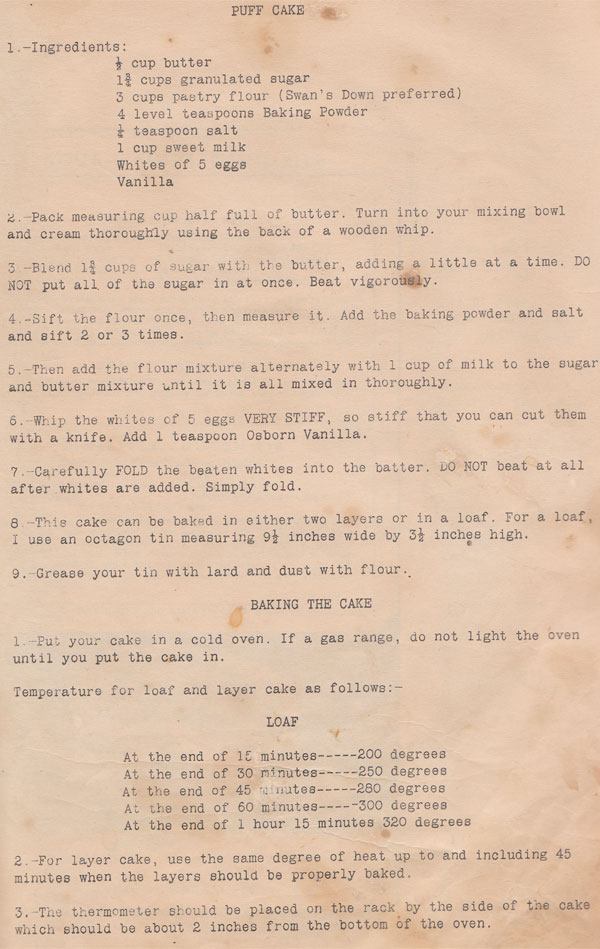

The handwritten recipe booklet that contains the recipe. Photo by Jess Tsang.

The handwritten recipe booklet that contains the recipe. Photo by Jess Tsang.

The notebook isn’t dated, it simply contains pages of recipes jotted down for safe keeping, including Ham Rolls and a ground beef dish called Hiker’s Hastener. Sometimes, a unique recipe like Limas with Marshmallows can help date a recipe book like this one. After searching Google Books, I discovered the recipe had been potentially been copied out of A Book of Practical Recipes for the Housewife, published in 1900.

One of the reasons this recipe caught my attention is because last Thanksgiving I looked into the history of Sweet Potato Casserole with Marshmallows. Marshmallows became a popular convenience food at the turn of the 20th century because new machines were invented that produced them cheaply and easily. Previously a delicate confection, marshmallows were now available for the masses. Recipe books pushed housewives to use them as substitutes for more labor intensive toppings like meringue and whipped cream.

The frist recipe for sweet potatoes topped with marshmallows appeared in 1917 or 1918 (read more here). But this recipe for lima beans topped with marshmallows appeared in 1900, which means there was a precedent for topping vegetables with marshmallows before they were plopped on sweet potatoes.

Are there other recipes for vegetables topped with marshmallows? Broccoli? Brussel sprouts? I’m not sure. I haven’t found them yet. But clearly this was a thing

The Recipe

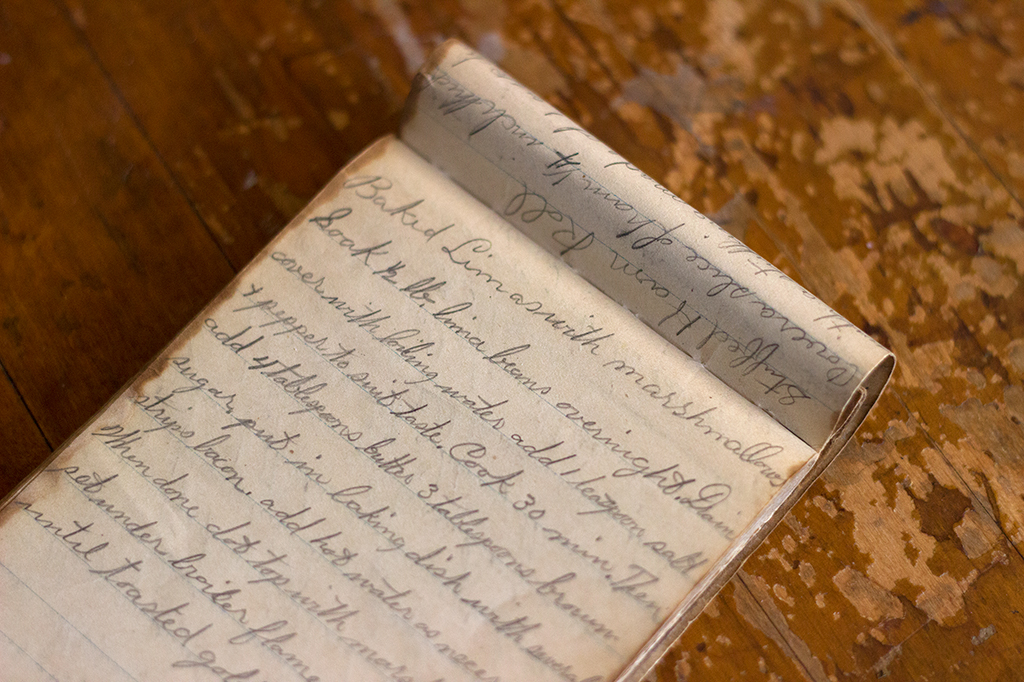

Baked Limas with Marshmallows, c. 1900. Photo by Jess Tsang.

Baked Limas with Marshmallows, c. 1900. Photo by Jess Tsang.

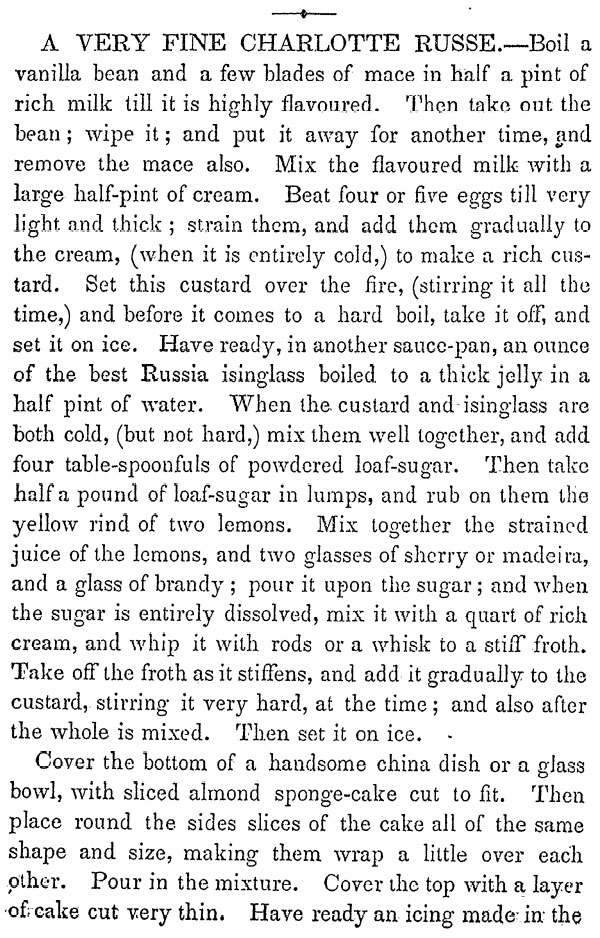

The only adjustment I made to the original 1900 recipe is that I used frozen lima beans. I just tossed them in the casserole with the ingredients, no pre-cooking necessary.

The Results

Ready for the oven! Photo by Jess Tsang.

Ready for the oven! Photo by Jess Tsang.

I have some good news and I have some bad news.

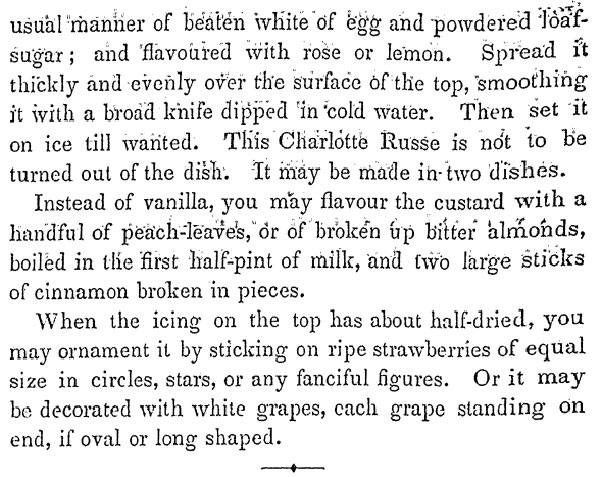

The good news: Lima beans, butter, brown sugar, and bacon is a GOOD THING. It is sweet, salty, and rich. The limas have a satisfying snap in your mouth, a salty smokiness from the bacon, and a mouth-covering fatty sweetness. My only advice: cook the bacon separately and mix it in just before serving. Cooking it on top of the casserole, as the recipe suggests, results in flimsy, flaccid bacons. If the bacon has been perfectly crispy little squares, crunching around in there with the butter and the beans…oh…it would have been heaven.

The bad news: Holy shit did those marshmallows just ruin everything. Basically, this recipe took a wonderful casserole and put marshmallows all over the top of it. The overwhelming sweetness, the sticky gelatinous texture…the entire taste and horrific mouth-feel was so shockingly unappealing it’s difficult to put into words. Just imagine how bad you think this recipe would taste, and then understand that’s actually how bad it does taste, and then don’t put marshmallows on any vegetables this holiday season.

So beautiful yet so horrible. Photo by Jess Tsang.

So beautiful yet so horrible. Photo by Jess Tsang.

This blog post was put together with a boatload of help from intern Jess Tsang. Thanks, Jess!

I love the way Susan brings these recipes to life.  Because they are handwritten, each recipe has its own individual character.  They seem to speak about the woman who sat down and penned them 75 years ago or more.

I love the way Susan brings these recipes to life.  Because they are handwritten, each recipe has its own individual character.  They seem to speak about the woman who sat down and penned them 75 years ago or more.

1. In a medium saucepan, heat water and isinglass, stirring constantly until isinglass has dissolved. Â The resulting liquid with be thick and tapioca like

1. In a medium saucepan, heat water and isinglass, stirring constantly until isinglass has dissolved. Â The resulting liquid with be thick and tapioca like