Pearlash is powdery and slightly moist.

The History

If you were to scoop the ashes out of your fireplace and soak them in water, the resulting liquid would be full of lye. Â Lye can be used to make three things: soap, gun powder, or chemical leavener.

A “leavener” is a substance that gives baked goods their lightness. Â Today, we think nothing of adding a teaspoon of baking soda or baking powder to our cakes and cookies. Â But using chemicals to produce the carbon dioxide necessary to raise a cupcake is a relatively new idea.

Before chemicals, cooks would use yeast. Â Not just in bread, but yeast was often added into cake batter, along with a helpful dose of beer dregs or wine. Â The alternative was whipping eggs to add lightness, like in a sponge cake, although that particular recipe didn’t become popular until the end of the 19th century, after mechanized egg beaters were introduce.

Sometime in the 1780s an adventurous woman added potassium carbonate, or pearlash, to her dough.  I’m ignorant as to how pearlash was produced historically, but the idea of using a lye-based chemical  in cooking is an old one: everything from pretzels, to ramen, to hominy is processed with lye.  Pearlash, combined with an acid like sour milk or citrus, produces a chemical reaction with a carbon dioxide by-product.  Used in bakery batter, the result is little pockets of CO2 that makes baked goods textually light.  Pearlash was only in use for a short time period, about 1780-1840.  After that, Saleratus, which is chemically similar to baking soda, was introduced and more frequently used.

I was curious to try this product out and see if it actually worked. Â I ordered a couple of ounces from Deborah Peterson’s Pantry, the best place for all your 18th century cooking needs. Â I used it during my recent hearth cooking classes in a period appropriate recipe.

The Recipe

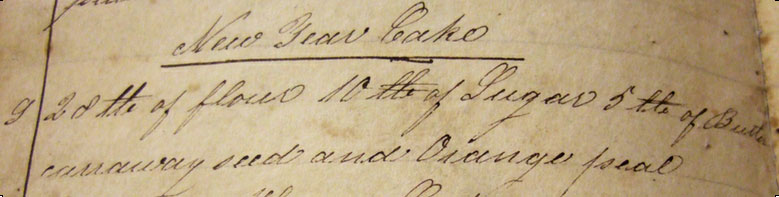

The recipe, for orange-caraway New Year’s Cakes, came from the cookbook-manuscript of Maria Lott Lefferts, a member of one of the founding families of Brooklyn. Â The use of pearlash, plus a recipe for “Ohio Cake,” serves to date this book to about 1820. Â It looks like this:

“New Year Cake

28 lbs of flour 10 lbs of Sugar 5 lbs of Butter

caraway seed and Orange pealâ€

This recipe doesn’t mention pearlash, but several of the other recipes in this book do. Â I checked the first cookbook printed in American, Amelia Simmon’s American Cookery, for an idea of how much pearlash to add. Â Here is the recipe I came up with:

New Years Cakes

Based on Marie Lott Leffert’s cookbook, c. 1820

1 cup light brown sugar, packed

1 stick salted butter

3 teaspoons pearlash dissolved in 1/2 cup milk

4 cups all purpose flour

Zest and juice of one orange

1 tsp ground caraway and 1 tsp whole caraway

Whisk together flour, zest and caraway. Â Beat butter and sugar until light and fluffy. Â Add orange juice and pearlash, then mix. Â Slowly add flour; mixing until flour is incorporated. Â Put in freezer one hour. Â Break off small pieces and roll very thin; cut with a cookie cutter or knife. Â Preheat oven to 300 degrees. Â Bake until cookies are slightly golden on the bottom, about 10 minutes.

***

Cookies leavened with pearlash come out of the oven.

Cookies leavened with pearlash come out of the oven.

The Results

I made the dough in advance and froze it, then dragged it to Brooklyn to be baked in a very period appropriately in a wood fire bake oven.

When the cookies came out of the oven, they had risen! Â They gained as much height, and as much textural lightness, as a modern cookie made with baking powder.

But how did they taste?  The first bite contained the loveliness of orange and caraway (for a modern version of this recipe, I highly recommend using this recipe, and replacing the coriander with orange zest and caraway).  But after swallowing, a horrible, alkaline bitterness filled my mouth.  My body reacted accordingly: assuming that I had just been poisoned, I salivated  uncontrollably.

At first, I wondered if I hadn’t used too much pearlash. Â But then something dawned on me: Â the earliest recipes to use pearlash were gingerbread recipes. Â Of the four recipes in Simmon’s cookbook, half of them were for gingerbread. Â A highly spiced gingerbread probably did a lot to hide the taste of the bitter base chemical.

And that’s why I like historic gastronomy. Â If I hadn’t actually baked with pearlash, and tasted it, I never would have made the gingerbread connection. Â There’s something to be said for living history.

I’ve been wanting to try baking with Pearl Ash for ages now . . . Thanks for the post!

It was an interesting experiment, but there is no advantage I saw over modern leavening. Give it a try and let me know how it goes!

I would love to know what the Ohio Cake consists of! Do tell!

I am out of town, but when I return to new york, I’ll look it up. It seemed like a pretty basic butter cake. I wonder whre the recipe came from–I imagine it being the official cake of Ohio’s statehood celebration.

You’re my hero! I once had a long conversation about pearlash with a chemist (actually, she was a metals conservator, for which chemistry is a strong prerequisite). I don’t recall how it came up, but I’m pretty sure we realized that pearlash had to be used along with an acid, like vinegar or lemon juice. I wasn’t clear whether that was meant to activate it, or perhaps to balance the taste? I seem to remember that it mattered when you added the pearlash and the acid as well, i.e. they went in together. Did you use the orange juice called for in the first receipt? If not, I wonder if that would help make future batches a little more edible. Or perhaps you aren’t eager to repeat the experiment ;-).

I think 1 teaspoon of pearl ash would have been quite enough. I know that if too much baking powder or soda are added the taste can be rather acidy. Yes, good old gingerbread cookies are great for masking taste, but make the soft kind, not the hard ones. Or make gingerbread cake.

When growing up we had dairy cows and gave them Black Strap Molasses which came in five gallon buckets. We would dip some out first to use in baking. This molasses has a very strong flavor and can pretty much match anything else.

Too much pearl ash and not enough acid ingredient. If you had used the same amount of modern baking soda the result would have been the same – terrible. Just because you are using historic recipes doesn’t allow you to leave common sense behind. The rules of chemistry and taste have not changed. The rule of thumb for baking SODA (not powder) is about 1/4 tsp. per cup so 1 tsp. would have probably been enough. And you should have used sour milk (buttermilk) for more acid.

It’s not clear to me why you would want cookies to rise in the first place, so the original recipe had no pearl ash. I’m sure Maria is giving you dirty looks from the grave, wondering why you messed up her delicious recipe.

My grandmother used to make wonderful raised sugar cookies from scratch. She didn’t have a recipe of which I was aware. She used an old gas stove to bake them. The aroma was wonderful and the taste, to my very young taste buds, was heavenly. They raised up very high in the middle and were not at all hard or crunchy, but had a soft almost bready texture. I miss them.

In any case. potassium compounds are known to have a bitter aftertaste. This is why pearl ash was replaced with the sodium based saleratus (baking soda). But using 4 x as much as necessary and not balancing sufficiently with an acid would surely make the bitter taste even worse.

Gingerbread was popular long before chemical leaveners appeared.

Informative comments, but they have a know-it-all tone. I’m sure that your legion of friends appreciate that–that you are such an expert on baking matters. So manly.

He appears to be the only one talking sense here!

pearl ash and baking soda are basic (ph > 7).

sour milk, vinegar, lemon juice are acid (ph < 7).

acid tastes sour.

basic tastes bitter.

"sour" and "bitter" are not quite the same.

So "…alkaline bitterness…" above is correct.

"not balancing sufficiently with an acid would surely make the bitter taste even worse." is correct.

but

"…too much baking powder or soda are added the taste can be rather acidy." is incorrect, has acid-sour, basic-bitter reversed.

Great blog! Are you sure pearlash was the first chemical leavening agent though? I thought hartshorn was used in baking as early as the 17th century.

I have to admit, I don’t know very much about hartshorn. It appears very rarely in American cookbooks; I don’t think we had the right kind of deer here, so importing it from Europe would be probably be prohibitively expensive. I thought perhaps the distinction was that pearlash had to be chemically manufactured, but hartshorn salts, used for baked, have to be “distilled.” So does that lump it in with yeast as a natural leavener, or is it the processing more like that of pearlash? I’m honestly not sure!

The declaration that Pearlash is the first chemical leavener originally comes from a different source–several in face. But now I’m going to do more research to find out if that declaration can be considered accurate!

Thank you! And cute panda.

Oh, I didn’t realise you meant first in America! In Marye Audet’s book The Everything Cookies and Brownies Cookbook she says “In the 1600s immigrants brought cookies to America. […] The leavener that was most often used was a type of ammonia made from the antlers of a deer.” but as you say there are plenty of other sources that claim pearlash is first, as it appears in the oldest American cookbook, printed in 1796. And at Cooks Info, it says “It appears that Hartshorn was being used for a gelatin in the 1600 and 1700s, and that only at the end of the 1700s did it start to be used as a leavener.” Who knows who’s right?

Dry distillation involves burning, much like how you obtain pearlash. But I would have thought that hartshorn would be classified as a chemical leavener not so much because of how it is produced, but how it works in your baking.

Thanks for the interesting posts. Am looking forward to reading more of them. :)

Yes! I thought I was crazy–my first reaction when you brought this up was “Isn’t Hartshorn a thickener?” I actually wad unaware it was used as a leavening, so I’ve been learning lots about it. And I did not specify “American” leavener in the article, so you are very right, too.

In the original American cookie recipes I’ve seen in manuscripts, they’re usually unleavened–they’re thin, crispy cookies. But I’m going to keep a lookout for a recipe that uses hartshorn so I can try it out.

Thanks for bringing this up!

That’s what I was wondering as I read through the comments – what would these be like without leavening… Why add leavening at all to cookies? Just for the textural variety?

A few sources say hartshorn wasn’t used as a leavener until the end of the 1700’s. http://www.godecookery.com/cookies/infoba.html

I wonder if anyone still makes it from antlers. I’d love to try some comparisons with pearlash and baking powder

For some reason, early “Christmas Cookie” recipes used pearlash. I think the texture would have been pretty mind blowing, because most cookies were more like butter shortbreads. Deborah Peterson’s Pantry used to sell hartshorn, but she retired, and I haven’t seen another source for it.

RE: the pearlash in Christmas Cookie question, I wonder if there is a correlation there between Albany’s prevalence in the potash market and the Dutch origin of Christmas cookies. Peter Rose is giving a book talk of her new Delicious December book at my site this winter, I’ll pick her brain about it!

Just look up Springerle Cookies. Hartshorn is the traditional leavener used in them, and as often as not Baking ammonia is still used in them.

Old German cookie recipe that can be traced back into the 1500’s.

Oh, THANK YOU for doing this so I can know without having to try it myself!

What an amazing blog – I’ll be sharing this with all my re-enacty friends.

NP:) It is worth experimenting with it, however–and learning from my mistakes!

This past weekend I was at an 18th century event that included a ladies’ tea and dance, and we were requested to bring something along if we were attending. Well, I have three children and this was the first reenactment for one of them, so just getting there this weekend was a mad scramble. So I brought pumpkin bread that my husband had made because honestly, if they want *everyone* to bring something they can’t be that fussy, can they?

I didn’t even go because I wasn’t feeling it, but offered to send the stuff in with my mother who was attending, and she fussed at me for it and left it behind! Next time I’m’a make something with some potash and send it along and see how she likes THAT.

This made me burst out laughing.

Helped SO much! I’m doing a science fair project on leaveners!

Happy to help!

I recently made springerle (medieval German pressed cookies), which use hartshorn to this day. You can get it in its baking form from House on the Hill, which specializes in springerle molds and supplies.

When I got the hartshorn and opened the package, I nearly fell over from the smelling-salts scent of it. It’s hard to believe it will not taste awful in the cookies.

However, you air-dry the cookies first, and then bake them very slowly at low heat, which allows the hartshorn to evaporate out of the cookies, eliminating the taste of ammonia.

I suspect that this is similar to what would have happened when using pearlash in gingerbread: dissolving it in acid first (both recipes I found using it tell you to do that, in sour milk or vinegar), and baking it longer than most things might do the trick.

Springerle also tend to be heavily flavored.

The recipe for gingerbread with pearlash specifically noted that you shouldn’t use lemon juice in the bread because pearlash “entirely destroys the taste of lemon-juice and of every other acid”.

Fascinating! And I am stunned to learned springerle still use hartshorn. This post was very educational for me.

I’m honestly surprised that you people are still alive after eating these things. OMG! LOL

Hartshorn is still used in Scandinavia for baking, mainly for cookies and you can buy it in any grocery store here. In Sweden it is called hjorthornssalt (deer horn salt). I found it in some cookie recipes and was delighted that such an old fashioned ingredient was still in use. But just now as I was searching (see link below) I was dissapointed to find that they no longer actually use real deer horn but a chemical substitute.

Here is a link with some recipes.

http://www.swedishfood.com/hjorthornssalt

I have long been fascinated by historical recipies and have been delighted to read your blog!

Thank you! have you ever tried experimenting with the real thing?

I have made a batch of cookies with the hartshorn that is readily available here and they turned out fine. I have only seen it mentioned in cookie recipies, so I think the harsh flavor that is mentioned would only come into play if you used large quantities like for a cake. If you feel that you really want to try it, I would be happy to mail you a packet, in the name of food science, if you send me your address.

Check out the youtube videos produced by James Townsend & Son, in which baking with pearl ash is demonstrated. The company, http://www.jas-townsend.com also sells pearl ash.

Pearl ash is a slightly refined potash. Potash was made in colonial times by soaking wood ashes in water, then boiling off the water. The residue left in the pan was potash.Potash and pearl ash were export commodities in colonial times. The English wool industry used potash to clean raw wool before spinning. At one point in upstate New York, the potash produced by an acre of woodland could be sold for more than the purchase price of the land, allowing cash-poor farmers a ready means for paying off their note.

As for cookies, I believe that word comes to us from the Dutch settlers of New Netherland (NY, NJ, and parts of Connecticut and Delaware), and according to the Oxford Dictionary of Food, Dutch bakeries in the Hudson River valley were using pearl ash in the 18th century, having brought knowledge of it from Holland (where it must have been in use even earlier.)

Hi, Sarah, really happy to have found your site. Should keep me me busy for a while.

I think John is correct about the Dutch having been (at least one avenue) for pearlash being brought into the colonies, and I have seen references to it being used by Dutch bakers as far back as the Middle Ages.

There is other way, often overlooked, that bakers got doughs to rise, which would be a lot of fun to experiment with. The origin of the Southern biscuit is often said to be “beaten biscuits,” a simple biscuit dough made with flour, lard, and milk. The dough was whacked repeatedly with some implement for up to thirty minutes. They would pound the dough, fold it over, pound it some more, etc. and this would form tiny air pockets, like blisters, in the dough. So, the biscuits would rise but of course, as you can imagine, this worked the gluten until the result was quite dense. You can still find recipes for this, especially if you look for “Maryland biscuits.”

Wonderful website, Sarah, so much food for thought! One of the few sites I have room in my inbox for!

Thank you so much for your comment (and compliments!) I actually experimented a bit with beaten biscuits, you can read about them here: http://www.fourpoundsflour.com/kitchen-histories-biscuits-you-can-beat-with-a-stick/

If you wish for to improve your know-how simply keep visiting

this website and be updated with the latest news

posted here.

Reading early recipe books always makes me wonder how many of the great advancements in culinary science have been unexpectedly happy results of the rampant adulteration of foodstuffs. “Hey Mr. Baker-Boss! We’re short on flour for today’s biscuit batch!” “Just dump the ashcan in there and mix it up – nobody will know.”

it was all right

I watch James Townsend and Son. He uses it a lot in his 18th century cooking.

http://www.townsends.us

I’ve lived in the same village in East Yorkshire since 1958,over the years I’ve realised there’s More for the name of this village, Leavening, Bear with me, they made glass here on an industrial scale, during the 14th 15th century before and after The glass for York minster was actually made here too along with a lot of the other abbeys feedrolls in England ,its also stated that they made bread here for the poor people, of which I found two bread ovens when I remodel the Family home which stands on the site of the original glass works,

The furnace was fired by wood, so the ash would be pure, so was this pearl ash used to raise the baking, The area where the pilgrim fathers departed from it’s only 45/50 miles south of the village , It’s also thought that there were ties with the Bonamy Richard Captain and the village at some point in history, my grandmother told of a story about a bed that as a wedding gift Bought by someone who went to America and Could not come back,

So I think there is something in the name and Suggests that pearl ash was the first rising agent Leavening,

I read an interview with a 76-year-old woman in Oregon done in 1938 where she talked about her mother in law (who was a pioneer and went out on the Oregon Trail) used “lye and ashes” to leaven sweetened breads. I was so puzzled until I started googling what she could be talking about. Went down the rabbit hole and it led me here. Also led me to a German website hartkorn-gewuerze.de which sells “cooking potash” and “hartshorn” both. Their blog has info on which to use when and the fact that you do not need an acid for leavening from potash, only a liquid, which I found interesting (if confusing).

Another old chemical leavening agent is tartaric acid, the basis of the “cream of tartar” in some formulations of baking powder. It was collected from wine dregs for this purpose. Some of those who prepared and sold it took the family name Weinstein, German for “wine stone,” i.e., the crystals that accumulated in wine. They were removed by decanting the wine from (guess what?) decanters, and figuring out how to prevent this stuff from accumulating in wine and making it cloudy was one of Pasteur’s first projects for the French vintners who hired him. Eventually, he figured out what happens during fermentation.