Black pepper-crusted steaks. Photo by Alan Tran.

Black pepper-crusted steaks. Photo by Alan Tran.

While writing my first book, Eight Flavors: The Untold Story of American Cuisine, I researched the eight most popular flavors in American cooking: black pepper, vanilla, chili powder, curry powder, soy sauce, garlic, MSG, and Sriracha. When I dived deep into each of these eight topics, I often found fascinating new information and recipes–some of which didn’t make it into the book. So over the next few months, I’ll be publishing this exclusive content on my blog! If it whets your appetite to read the whole book, make sure to get your own copy here.

When we cook a steak, we often cover it in a thick layer of cracked peppercorns and salt. A simple, but flavorful, preparation. This generous crusting of pepper is often credited to a trend born of the 1960s, with a dish called steak au poivre. But the roots of this classic steak preparation may go back much further.

Martha Washington’s Booke of Cookery is a manuscript collection of recipes, gifted to Martha on the occasion of her first marriage to Danial Custis. The recipe book– copied from recipes of her in-laws–includes recipes that date from the late medieval era to the early 18th century. One in particular caught my eye: a roast of venison crusted in black pepper.

To Season a Venison

Take out ye bones & turne ye fat syde downe upon a board. yn take ye pill of 2 leamons & break them in pieces as long as yr finger & thrust them into every hole of yr venison. then take 2 ounces of beaten pepper & thrice as much salt, mingle it, then wring out ye juice of lemon into ye pepper & salt & season it, first taking ye leamon pills haveing layn soe a night. then paste it with gross pepper layd on ye top & good store of butter or muton suet.

Here’s a rough translation of the recipe: De-bone a roast of venison. Take the peel of two lemons and cut it into finger length strips, stuffing them into any holes left from the bones. Let the meat sit overnight, and remove the lemon peels. Take two ounces ground pepper and six ounces salt, mixed with the juice of one lemon, and season the holes the lemon peels previously occupied. Crust it with cracked pepper and butter or fat.

Sounds like the great-great-granduncle of a modern steakhouse dish, doesn’t it? This pepper-heavy treatment of venison was recommended through the 19th century to offset the strong, gamey flavor of the meat. The salt and fat would also serve to keep moist what was a particularly lean, dry meat. By the end of the 19th century, this dish evolved to have a creamy, pepper sauce, or sauce poivrade, and became known as “Steak a la Diane,”named after the Roman goddess of the hunt. The renowned Auguste Escoffier gave us a recipe for pepper sauce intended for venison in Le Guide Culinaire, published in 1903.

Sauce Diane

Lightly whip 2dl [about 2 cups] of cream and add it at the last moment to 5dl [4 1/2 cups] well seasoned and reduced Sauce Poivrade. Finish with 2 tbs each of small crescent shaped pieces of truffle and hard-boiled white of egg. This sauce is suitable for serving with cutlets, noisettes and other cuts of venison.

His sauce was comprised of three other sauces and stocks, each one slowly simmered from finely diced vegetables and joints of meat to add levels of deep flavor, and finished with slices of truffle. The entire dish, rich with pepper, would have taken an army of kitchen staff days of preparation before it finally landed in front of a restaurant patron.

French chefs simplified the dish after the turn of the century, calling it “steak au poivre†for the first time. Venison steak was replaced with crushed peppercorn-encrusted beef, which was pan seared and served with a brandy, butter, and (sometimes) cream-based sauce. The dish was often cooked table-side because when the brandy was added to the hot pan it resulted in an impressive tower of vaporized alcohol flames.

In the 1960s, American home cooks were introduced to the cuisine of France by Julia Child. Child’s longtime friend Jacques Pépin remembered her in the New York Times as “… almost a foot taller than I and her voice was unforgettable — shrill and warm at the same time.†They loved to disagree and debate proper cooking techniques and ingredients; “I like black pepper and she liked white pepper,†he recalled. According to Pépin, Child’s style of cooking meant “a simple meal made with great care and the best possible ingredients.†Her strong opinions on food come through in her recipe for steak au poivre. Child’s 1961 recipe for steak au povire in Mastering the Art of French Cooking was the first to be published in America, but she speaks to her readers as though the recipe was a familiar one, a nod to its pre-existing popularity in restaurants.

Julia Child.

Julia Child.

“Steak au poivre can be very good when it is not so buried in pepper and doused with flaming brandy that the flavor of the meat is utterly disguised,†Child writes. “In fact, we do not care at all for flaming brandy with this dish; it is too reminiscent of restaurant show-off cooking for tourists. And the alcohol taste, as it is not boiled off completely, remains in the brandy, spoiling the taste of the meat.” As a rule, she felt “there was too much flaming in table top cookery.â€Â In Child’s recipe, after the steaks are seared a sauce is made with leeks and crispy cooked bits left in the bottom of the pan, as well as vegetable stock, cognac and a lot of butter. The peppercorns crisp into a crust, and the dish is served with potatoes to soak up the rich sauce.

Through Mastering the Art of French Cooking, steak au poivre entered the American mainstream and set the precedent for how we prepare beef; a perfect example of Julia Child’s tremendous culinary influence. The dish is also key in shaping our modern identity of pepper. Steak au poivre treats pepper not as just another spice to be shaken into every dish, but as an ingredient with a bold flavor all its own. Steak au poivre today influences how most Americans cook their meat: crusted in salt and pepper, seared and served. The most basic cooking technique, and perhaps the most delicious.

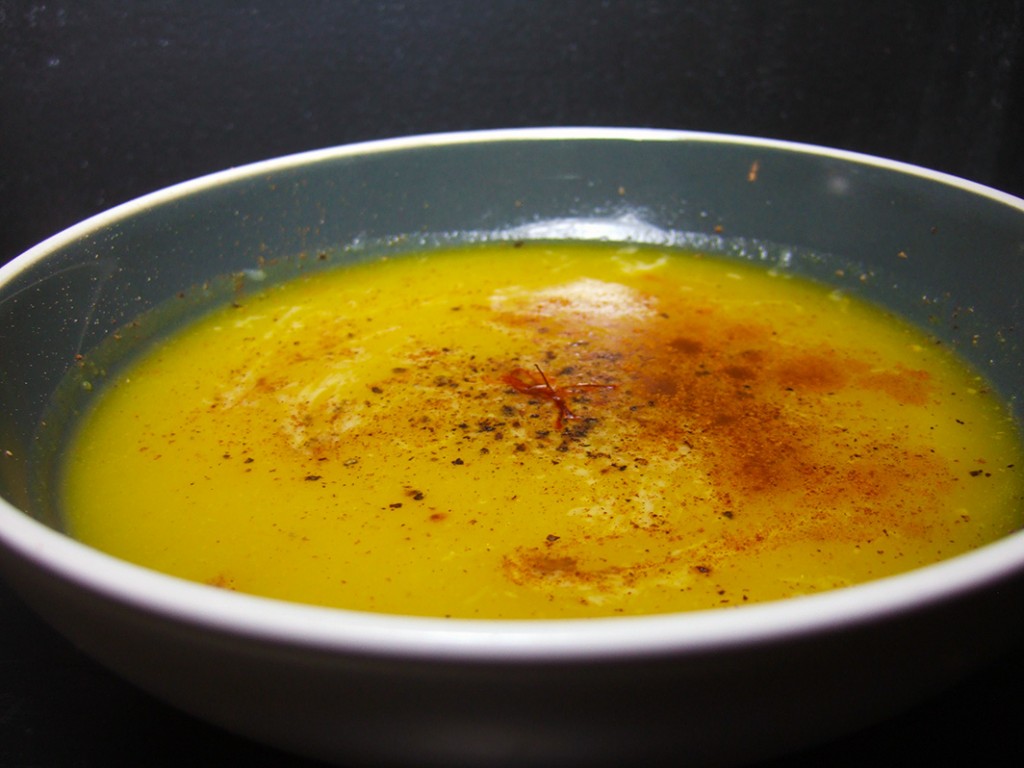

Steak au poivre. Photo by mmmWolf.

Steak au poivre. Photo by mmmWolf.

Steak au Poivre

From Mastering the Art of French Cooking, 2011 reprint, by Julia Child, Louisette Bertholle, Simone Beck

2 Tb of a mixture of several kinds of peppercorns, or white peppercorns

Place the peppercorns in a big mixing bowl and crush them roughly with a pestle or the bottom of a bottle.

2 to 2 1/2 lbs. steak 3/4 to 1 inch thick

Dry the steaks on paper towels. Rub and press the crush peppercorns into both sides of the meat with your fingers and the palms of your hands. Cover with waxed paper. let stand for at least half an hour; two or 3 hours are even better, so the flavor of the pepper will penetrate the meat.

A hot platter

Salt

Sauté the steak in hot oil and butter as described in the preceding master recipe. Remove to a hot platter, season with salt, and keep warm for a moment while completing the sauce.

1 Tb butter

2 Tb minced shallots or green onions

1/2 cup stock or canned beef bouillon

1/3 cup cognac

3 to 4 Tb softened butter

Sauteed or fried potatoes

Fresh water cress

Pour the fat out of the skillet. Add the butter and shallots or green onions and cook slowly for a minute. Pour in the stock or bouillon and boil down rapidly over high heat while scraping up the coagulated cooking juices. Then add the cognac and boil rapidly for a minute or two more to evaporate its alcohol. Off heat, swirl in the butter and half-tablespoon at a time. Decorate the platter with the potatoes and water cress. Pour the sauce over the steak, and serve.

The perfect flank steak.

The perfect flank steak.

Julia Child.

Julia Child.