Recently, a friend asked me my opinion on why we write recipes::

I came across an article on a friends blog today (read the article here) and it made me curious. She’s first generation chinese and says her family (and the chinese in general) don’t really use recipes. I’ve found the same thing with my bubbe. It’s pretty maddening, we’ve been trying to record her “recipes” for posterity for years to no avail…Curious if you think “recipes” are a more anglo-european thing???

I think it’s generational. The “bubbe” and the Chinese grandmother in question were both immigrants.  They grew up in a pre-industrial environment where the family group lived in close proximity to each other.  Children learned to cook at the side of their mothers or grandmothers. There was no need for recipes, because the techniques were shown and passed down through oral tradition.

That would change as families split to move across oceans, or even from the countryside to the city. Cook books became popular because America industrialized (starting in the mid-19thc), which means newlyweds were moving to the city to get jobs, which removed brides from the sides of their mothers. So suddenly women couldn’t learn cooking from their mothers or grandmothers, and needed a resource they could take with them: written recipes.

So I think it has less to do with anglo vs jewish or chinese, but perhaps industrialized worlds vs. pre-industrial. And perhaps the answer to trying to transcribe our grandmother’s recipes–which people ask me about all the time–isn’t trying to write them down for quick reference, but taking the time to cook beside our grandmothers everyday and learn their recipes through making it again and again.

What do you think?

I asked my kids what they think my signature dishes are and it was hard for them to be specific. I cook a wide variety of dishes from many different cultures weekly. I need recipes as a foundation. My Polish mom rarely ventured from the foods she grew up with and often did not use recipes. I would consider my cooking style to represent growing up in California and being exposed to many different foods through friends and curiosity.

What a great point–today, recipes allow us to experiement with unfamiliar foods from different cultures. I imagine it was similar for an adventerous cook in 1840s American who wanted to try a chicken curry. Hadn’t thought of that!

Historically I thought recipe or receipt books were for daughters to carry on family recipes and were an alternative to pressing flowers and embroidery. I mean how many working class mothers made recipe books ?

For myself I make notes for my own record and inspiration or to start new projects. Nobody will get to read them.

Paul

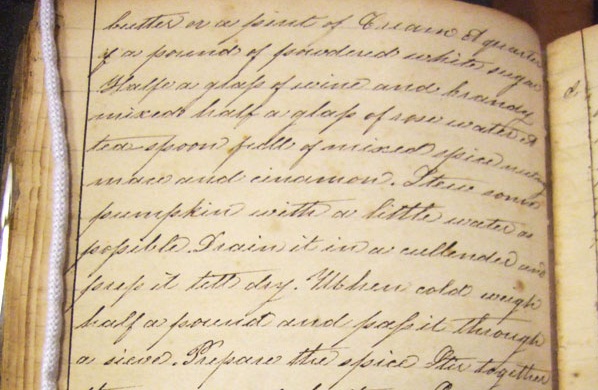

Hmm…and of course there’s a difference between a handwritten cookbook and a commercially available one. Yes, most of the earliest American “cookbooks” come from family manuscripts, some as old as the 17th century. Interesting to think about!

I have a 1930’s kosher cookbook that belonged to my husband’s great-grandmother, 1/2 in English and 1/2 in Yiddish. While it was published by Manischewitz (and uses matzos or matzo meal in every recipe), and should probably be considered more of an advertisement, it is definitely a Jewish cookbook!

Personally, there are a few things that I make so regularly that I no longer need to look at a recipe. But if I’m cooking something new and unfamiliar, then much like Karen mentioned, I need a recipe to help me along the way. I think it’s much more a question of what you’re cooking, where you learned it, and so on, than it is a question of culture. (Literacy may also have played into it in earlier years, though.)

I had not thought about the literacy issue!! Also, I have cooked from that cookbook!

Schmaltz Cookies: history-dish-mondays-cooking-with-schmaltz-part-one

Pie Crust: http://www.fourpoundsflour.com/the-history-dish-matzo-meal-pie-crust/

Featherballs: http://www.fourpoundsflour.com/history-dish-mondays-featherballs/

The full cook book is available online here:http://openlibrary.org/books/OL22870158M/Ba'%E1%B9%ADam'%E1%B9%ADe_Yidishe_maykholim

Have you made any of the recipes?

I guess I wasn’t reading your blog back in 2009! :)

We’ve cooked from it a number of times actually. Squash “Souffle”, Matzo Pancakes (#4), and Cheese Balls. We’ve also made mock sausage, spinach pancakes, and a few other things that I didn’t bother blogging (yet). It’s kind of hit or miss what’s going to taste good, but always tons of fun to try.

Hi, interesting post! I think if you are cooking/dabbling in different cuisines like a lot of people do now, there’s no way you could with out relying on recipes–if you are cooking a traditional cuisine there’s a smaller universe of ingredients to keep track of I think. At least I never could. There are of course certain dishes that appear in different guises in different cultures that are at root the same, aren’t there? So interesting. As for the industrialization as spurring on recipe books, that makes sense–and could explain why old recipes are so hard to use sometimes–they are really more like reminders or crutches rather than actual recipes and really presume you already know how to make it!

Yes! Early, handwritten recipes are often just lists of ingredients. More of a reminder, than what we consider a recipe. Not only can these old books go from mother to daughter, but they also often represent a community. One woman goes over to her neighbor’s to get her recipes for so-and-so and records it in the margins of her cookbook.

Fantastic topic (as usual)! My two cents is that the advent of written receipts in general, but especially cookbooks, was really helped along during the first half of the 19th century by rising rates of literacy, particularly among women; vast improvements in the production machinery for printing cheap books; and, as you already pointed out, the rising industrial middle class who suddenly wanted to impress their guests with something more than boiled hash. I often wonder exactly what the newly popular French sauces, etc. tasted like when made by an Irish cook, guided by an American housewife eagerly clutching Mrs. Beeton’s latest tome, neither of whom had ever seen such dishes before!!

I had not of literacy accounting for it! It’s interesting then, to think of literate cooks. The rising middle class perhaps meant that the household was buying cookbooks and then passing them off to their cooks to make the recipes.

Didn’t something like that happen in Downton Abbey?

Emily Dickinson grew up beside her mother, who taught her to cook and bake, and they lived together their whole lives. She, nevertheless, kept recipes of her prize-winning breads and cakes (and exchanged recipes with aunts and cousins). The form of a recipe was an influence on Emily Dickinson’s poetic form; cooking and baking terms are used in many poems.

To get back to your question of why we write recipes. I write them if something turned out really well and I’d like to replicate it again. I ask for the recipe, or list of ingredients, when I like what someone else has cooked for me. Isn’t it the highest compliment?

Yes! There’s a great book all about cookbooks called “Eat My Words” and it specifically talks about cookbooks as a representation of community. We write a recipe down when we like something our neighbor/friend/relative made.

I’ve had Emily’s Black Cake. It was not bad–very 19th century: http://www.fourpoundsflour.com/?s=emily+dickinson

Had an idea for why we should write recipes.

These are the recipes I wooed your mother/father with.

The spaghetti bolognese from the freezer we had as I had no money to take her out. The perfect roast chicken to show I could cook more than mouth scorching food. Chicken a la crema as I had to cook the leftovers.

I am sure you get the drift.

Its a worthwhile project

Pau

There was an article in Gastronomica a couple issues ago about a column in the early Esquire magazines all about men cooking as a way to woo women. Until they were married, at which point they should give it up. ;)

Too late. Now divorced. She never learnt to cook. Or wash up. Or be tidy.

Looking for another victim now I suppose.

Paul

I ԁоn’t even know how I ended up here, but I thought this post was good. I don’t know who

уou are but cегtainly уоu’re going to a famous blogger if you are not already ;) Cheers!

OOOOOOF

oof