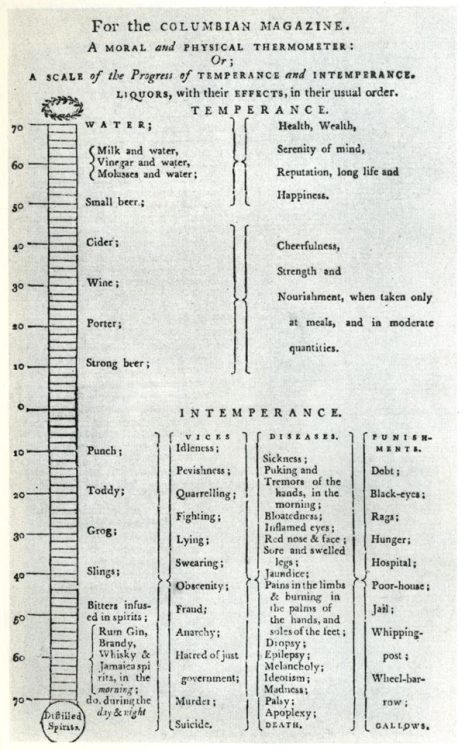

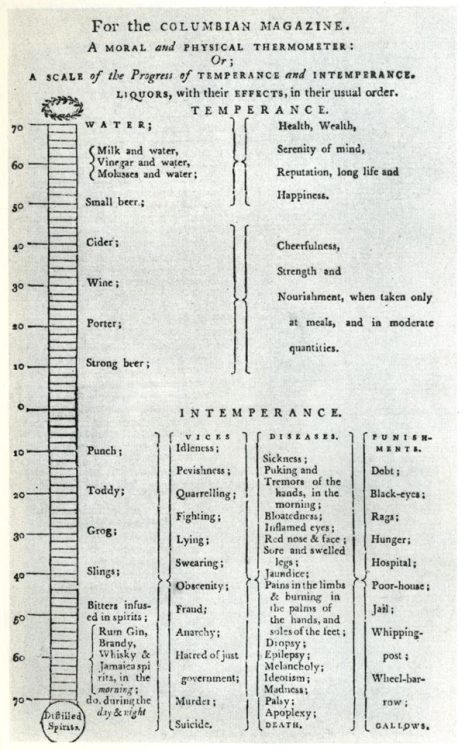

Dr. Benjamin Rush’s “Moral and Physical Thermometer,” published 1789

What am I up to? Read this introduction to understand the plan.

8:30am:

I have to start my day by “taking my bitters.” Bitters, infusions of herbs in spices in high proof alcohol, started out as health tonics. Starting the day with an “eye-opener” of spirits, water, sugar and a healthy dose of bitters was not only considered socially acceptable, but good for you. In fact, the first drink to ever be called a “cock-tail” was exactly this concoction, using whiskey for the spirit. And that’s how I’m started my day today, using an 1833 recipe for the original cocktail, as it appears in David Wondrich’s book Imbibe!: From Absinthe Cocktail to Whiskey Smash

1 tsp sugar

2 oz whiskey

3 oz water

4 dashes bitters

Nutmeg

Muddle sugar with water until dissolved. Add whiskey and bitters. Stir. Top with grated nutmeg.

I grabbed the first whiskey I saw in the liquor cabinet, which was Old Crow. Only after I made my drink did i realize we had a Buffalo Trace corn whiskey, that would have been more period appropriate because it was un-aged.

My boyfriend demanded to join me from under the comforter on the bed. I fixed him a drink, and he sat sleepy-eyed on the edge of the bed holding it.

“Well, what are you going to do now that you’re awake and drinking bourbon?”

“I don’t know…vomit?”

Running Total: 2 oz of hard spirits consumed @ 80 proof

8:51 am:

I realized I made our drinks with one oz of water instead of three. Whoops. So we are just drinking bourbon on an empty stomach.

9:38 am:

Had a tankard of hard cider with breakfast (eggs, bacon, toast). John Adams, an ardent temperenace supporter, had a tankard of cider with breakfast every morning. It wasn’t cider, beer, or wine that was considered “alcoholic,” it was distilled spirits considered ruinous to the working man (see above chart).

Cider was the American drink–scholars believe that Americans consumed more alcohol through hard cider than the much more potent spirit, Rum. The desire for hard cider didn’t subside until the temperance movement convinced many farmers to cut down their apples trees. Thankfully, events like Cider Week are bringing attention back to New York State growers and distillers.

11 oz of hard cider @ 10 proof. Running Total: 3 units of alcohol.

Yes. I’m a little drunk. Time to take a shower and get some work done.

11 am:

It is now the “elevens”!!! The Colonial American version of a coffee break! A hot toddy is appropriate at the elevens when the weather is cold, so I’ve decided to make apple toddys, one of the first cocktails to be recorded in print. I baked apples with “apple pie spice”, sugar and butter; then added them to hot water and apple brandy. I used apple brandy from Warwick Valley Winery, and from Laird’s who received the very first distiller’s license after the Revolutionary War.

I have not managed to take a shower yet. Let’s be honest here: if colonial Americans drank like this every day, their tolerance would be quite high. I will be drunk, but the Common Man in 1780 would have just been getting started.

I am trying to drink a glass of water between every drink.

2 oz of apple brandy @ 80 proof. Total: 5 units of alcohol in 2.5 hours.

11:40: am:

Where has the time gone? I have still not showered. I know I am drunk because everything is a celebration: “yaaaaay! It’s time to water the plant!!!”

12:22 pm:

Trying to sober up a little before lunch. IN the meantime, there was an interesting thread on Facebook yesterday regarding Colonial drinking, and I wanted to share some of the highlights.

R: All I can say is that I’d hate to be Sarah the morning after tomorrow! They also drank fortified wines (in 18th and 19th centuries) which get you crazy-drunk. I’ve heard a lot of people say that everyone drank ale, even children, because the water wasn’t potable. That may be true if you got your water from Collect Pond, but rich people would have had their own wells. I think they just liked tying one on.

Me: I don’t buy the “safer than water” excuse. In NYc — possibly. But the rest of the country was not so densely populated, and America was known for good quality water. That’s why everything we brewed/distilled was so delicious! I think the bottom line is grain and apples are worth more as liquor; and this is also a time when we had little else to drink but water. Alcohol provided variety, that today we replace with soda and fruit juice. Also true about the beer–but it was brewed at home, and only slightly alcoholic. More like today’s fermented sodas.

D: That’s a good point about water availability in America. But I wonder if the prevalence of cider was partly a continuation of European standards, though. In Europe, there was very little clean drinking water, so people might have just thought that alcohol was healthier than water. And even in New World, a lot of clean streams wouldn’t have stayed clean for long once settlers arrived.

Me: I think it’s a myth. I think it has more to do with financial reasons. Grain and apples go bad. Spirits and cider not, and you can sell the latter for more than the former.

D: Is there anything we know about what the colonists *did* think about nutrition, including the nutritional aspect of booze? I mean, there must have been some as-far-as-they-knew medical knowledge and folk wisdom about what foods you had to eat in order to be healthy. Did they think of spirits as having some kind of common nutritive properties with grain, such that one was a decent substitute for the other?

Me: I don’t know a ton about the topic, but I do know that “small” beer (home brewed, weak), cider, and wine were considered healthy, nutritive drinks that brought wealth and happiness, while distilled spirits would be the ruin of the working man. Dr Benjamin Rush was an early temperance advocate, and he made this great chart of what will happen to you if you drink various alcohols in various quantities (see above).

Thoughts?

1:19 PM:

I’m hungover and its painful.

2:11 PM:

Managed to get to the grocery store for more cider and a DiGiorno pizza. The lady at the store wished me a happy birthday (it’s the 15th) and I responded “You too!”

Having another cider with lunch. Here’s my line up for the rest of the day:

Throughout America, early afternoon dinner was accopanied by hard cider or distilled spirits mized with water; in later afternoon came another break; then supper with more refreshment. Finally, in the evening it was time to pause and reflect upon the day’s events while sitting by the home or the tavern fireside sipping spirits. (The Alcoholic Republic: An American Tradition , W.J. Rorabaugh)

, W.J. Rorabaugh)

Ugh. My head hurts.

12 oz of cider @ 10 proof. Total: 6 units of alcohol in 6 hours.

4:13 pm

After my last hard cider, my boyfriend and I sat down to watch The Brave Little Toaster. We promptly fell asleep. Now that I’m awake, I’m clearly sober, clearly hungover, and I have a sickening migraine.

To be honest, I’ve walked this weird tightrope between sobriety and drunkeness all day. Consuming so much alcohol so early in the day, on an empty stomach, is a surprsingly unpleasant feeling. It’s honestly not what I expected. I thought since the alcohol was spread out through an entire day that I would feel pleasantly buzzed, and not much more, as I Colonial drank away the hours.

I’ve taken my migraine meds and I’m trying to decide if the experiment should go on or if I should call it. I still have afternoon drinks, dinner drinks, and after dinner drinks to go.

5:29 PM

My brother just texted to point out that I’m halfway through, and I’m already on step six in the Drunkard’s Progress: Poverty and Disease. It’s only a short step down until I’m forsaken by friends.

I am trying to drink what a man’s portion of booze for a day would be. Here’s what Rorabaugh has to say about the ladies:

While men were the heartiest topers, women were not faint-hearted abstainers. Little, however, can be learned about either the reputed 100,000 female drunkards or the more numerous women who consumed for one-eighth to one-quarter of the nation’s spirituous liquor. The subject received scant attention because it was ‘too delicate’ to be discussed. The ideal of femininity did discourage tippling, for a woman was supposed to show restraint consistent with virtue, prudence consonant with delicacy, and a preference for beverages agreeable to a fragile constitution. The public was not tolerant of women drinking at taverns or groceries unless they were travellers recovering from a day’s arduous journey. Then the ladies might be permitted watered and highly sugared spirituous cordials.The concept of feminine delicacy led women to drink alcohol-based medicines for their health; many who regarded spirits as ‘vulgar’ happily downed a highly alcoholic ‘cordial or stomach elixir.’

See, I’m doing this for my health!

5:48

That’s it. I’m calling it. I can’t continue. I know I’m going to get a lot of shit from my friends for now being able to go the distance, but I feel HORRIBLE. I suspect it’s the hard cider, which I’m not used to drinking. Something didn’t agree with me, perhaps.

Even if I hadn’t gotten a headache, I don’t think I could have done the whole day.

I haven’t drawn any conclusions about my experiences yet. Let me dwell on it for a bit.

Masters of Social Gastronomy: Strange Meats!

Masters of Social Gastronomy: Strange Meats!

On a recent chilly evening, while the sun set over the 7x train somewhere in Queens, I descended from the rattling train track platform to meet with Autumn of

On a recent chilly evening, while the sun set over the 7x train somewhere in Queens, I descended from the rattling train track platform to meet with Autumn of

Pre-Industrial Dinner

Pre-Industrial Dinner

From the Buca di Beppo

From the Buca di Beppo